Sign up for the free Nautilus newsletter:

science and culture for people who love beautiful writing.

As of 2023, it is estimated that some 6.92 billion smartphones, and a further 7.33 million mobile phones, are in use worldwide. Via these pocket-size devices users can, at the touch of a button, converse with others scattered all over the world. With such a luxury now commonplace, it is easy to forget that not so long ago the concept of the telephone was merely science fiction. For Alexander Graham Bell, however, instant long-distance communication was inevitable, and a future he intended to personally bring about.

From a young age Bell was surrounded by conversations and ideas of sound and hearing. Both his father and paternal grandfather were elocutionists, but it was his mother’s hearing loss during his childhood which impacted his understanding of sound the most. Eliza Grace Bell had been rendered partially deaf due to scarlet fever as a child, and in adulthood her hearing gradually worsened.

Consequently, Eliza learned to lip-read in several languages, and taught her children to use a manual finger language which enabled her to participate in household conversations more easily. Bell even developed his own method of communication with his mother, which involved speaking directly onto Eliza’s forehead, so that she could feel the reverberations of sound and hear more clearly.

“The day is coming when telegraph wires will be laid on to houses just like water or gas.”

Much of Bell’s life and career was spent investigating the transmission of sound through electricity. His experiments with transmitting multiple messages via telegraph—a system of sending messages in the form of electrical pulses along a cable through a code of shorter and longer pulses known as Morse code—led him to conceive the idea of a device which could transmit human speech electrically: in other words, a telephone.

Bell’s telephone consisted of a transmitter and a receiver connected by a long wire. Speaking into the transmitter caused the flexible diaphragm to vibrate, varying an electrical current carried along the wire to the receiver, which worked in reverse, reproducing the sound waves and replicating the speech. At first these telephones could only work across short distances, but they were quickly developed with amplified power.

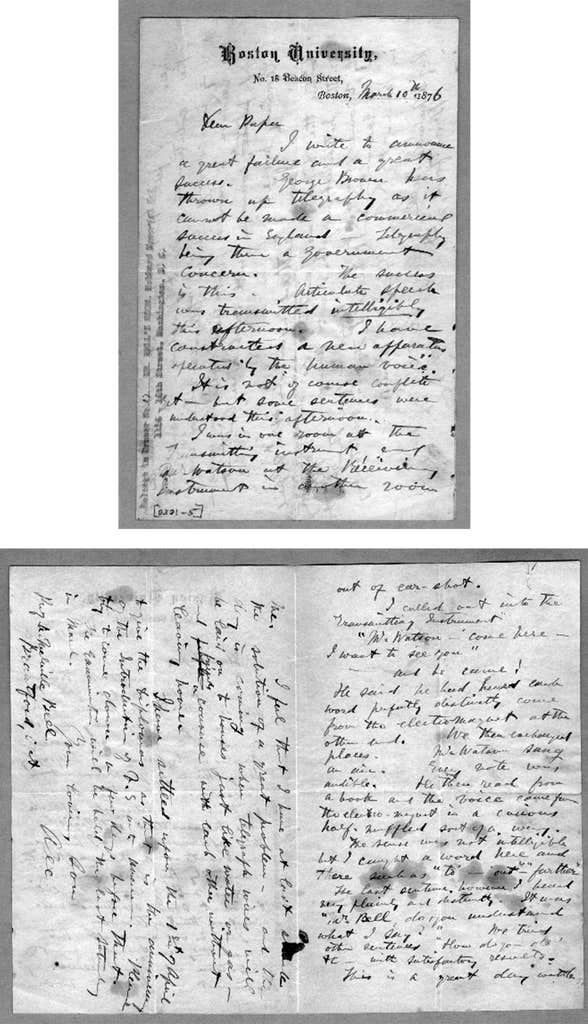

The first successful telephone call was made on March 10, 1876 between Bell and his assistant, Thomas Watson, sitting in an adjoining room. In this letter to his father written on the same day, an elated Bell expresses his joy at achieving this breakthrough, and shares his grand vision for the future of the telephone.

From Alexander Graham Bell to his father, Alexander Melville Bell, 1876:

Boston, March 10th, 1876

Dear Papa

I write to announce a great failure and a great success. George Brown has thrown up telegraphy, as it cannot be made a commercial success in England—Telegraphy being there a Government concern. The success is this. Articulate speech was transmitted intelligibly this afternoon. I have constructed a new apparatus operated by the human voice. It is not of course complete yet—but some sentences were understood this afternoon.

I was in one room at the Transmitting Instrument and Mr Watson at the Receiving Instrument in another room—out of earshot.

I called out into the Transmitting Instrument, ‘Mr Watson come here—I want to see you’—and he came!

He said he had heard each word perfectly distinctly come from the electromagnet at the other end. We then exchanged places. Mr. Watson sang an air. Every note was audible. He then read from a book, and the voice came from the electro-magnet in a curious, half-muffled sort of way.

The sense was not intelligible, but I caught a word here and there such as ‘to ’— ‘out’—‘further.’

The last sentence, however, I heard very plainly and distinctly. It was, ‘Mr. Bell, do you understand what I say?’ We tried other sentences, ‘How do you do?’ and etc., with satisfactory results.

This is a great day with me. I feel that I have at last struck the solution of a great problem—and the day is coming when telegraph wires will be laid on to houses just like water or gas—and friends converse with each other without leaving home. I have settled upon the last of April to give the diplomas, as that is the anniversary of the Introduction of Visible Speech into America. Please try to come down a few days before that.

The Examination will be held the last Saturday in March.

Your loving son, ALEC Prof. A. Melville Bell Brantford Ontario

Excerpted from Letters of The Ages Great Scientists, reprinted with permission of the author, courtesy of Bloomsbury Continuum, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. Copyright © 2024

Lead image: Alexander Graham Bell family papers, 1834-1974.

-

James Drake

Posted on

James Drake is an entrepreneur, philanthropist, and the founder at Of Lost Time, an innovative literary unit which uncovers the hidden stories of the past through the power of personal correspondence. He is also a co-editor of Letters of The Ages Great Scientists.

-

Hugh Aldersey-Williams

Posted on

Hugh Aldersey-Williams is the author of the bestselling Periodic Tales—a cultural history of the chemical elements. He is an author, journalist, and columnist. He is also a co-editor of Letters of The Ages Great Scientists.

Get the Nautilus newsletter

Cutting-edge science, unraveled by the very brightest living thinkers.