As a father of six children, Utah state Sen. Kirk Cullimore is no stranger to the joys and rigors of parenting. His youngest is 9 years old, and his oldest is 20, just entering early adulthood.

And yet, as the years go by, one parenting challenge has remained stubbornly constant for him and his wife, Heather: their kids’ ever-present phones.

When it comes to setting limits on his children’s screen time, Senator Cullimore says he has fallen short. The Republican lawmaker suspects he is not alone – and that’s just one reason he helped make Utah the first jurisdiction in North America last year to pass legislation attempting to limit kids’, and especially students’, access to social media.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

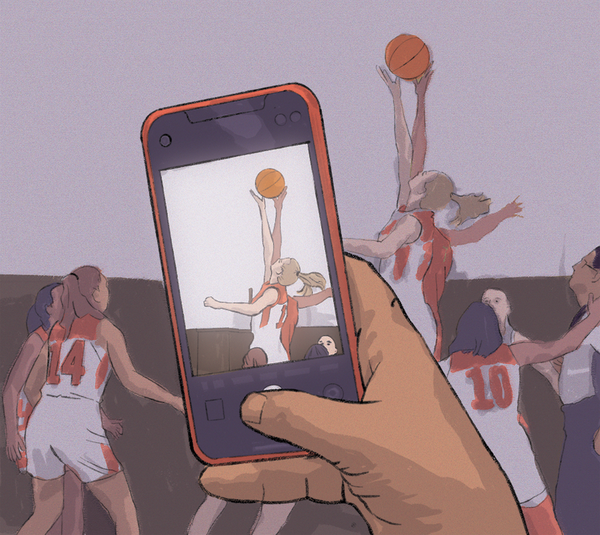

Cellphones and social media are taking over childhood, a growing consensus of parents and public officials says. Leaders in Canada and the United States are taking legal action.

“Some parents do think they’re doing a good job,” he says. “If you’re doing a good job, kudos to you and great job. But the reality is that there are many of us who are trying, and it’s too big of a problem.”

On a hot day in the suburban Salt Lake City district Senator Cullimore represents, five of his six children gather around a conference table in his law office to talk about their experiences. Their phones are nowhere in sight.

For the next hour they discussed the good, the bad, and the ugly of their social media habits. Ordinarily, they say, being without their screens would be an agonizing ordeal for them.

But the family has just returned from an Alaska cruise that had spotty internet connection. The involuntary hiatus from the digital worlds they inhabit so often wasn’t easy. But they appreciate how it made them prioritize hanging out with each other and their cousins.

Jackie Valley/The Christian Science Monitor

Utah state Sen. Kirk Cullimore and his wife, Heather (at center), stand in his law office in Draper, Utah. They are surrounded by five of their six children: (from left to right) Kapri, Kobe, Kya, Keeley, and Kynda.

After the cruise, when they could finally get service at the airport, the allure of logging on to Instagram didn’t feel so strong, says 16-year-old Kapri. “I was like, ‘Cooool,’” she says slowly, with a pantomime of surprise. “It wasn’t that important.”

Her father knows these reactions might not last very long. And the discussion is important. But it’s going to take a lot more to address the amount of time young people devote to social media. “We need everybody,” Senator Cullimore says.

An untamed beast

Indeed, more and more parents, educators, and lawmakers are starting to view the problem as an untamed beast. As a result, there has been a sea change in public sentiment across the United States and Canada, about kids and their smartphones. There’s been a growing sense that social media is changing, and in some ways robbing, children of their childhood.

Utah’s pioneering efforts last year helped open the floodgates to a wave of legal efforts to address the amount of time children and teens spend glued to their phones.

Experts say it has been a watershed moment, akin to major shifts around other health issues such as tobacco use. By the end of last year, at least a dozen U.S. states had approved laws or enacted resolutions seeking to minimize social media harm among their youngest users, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Many other states are poised to pass even more this year.

“Like seat belt laws and tobacco regulations enacted years ago to protect our physical health, and especially our kids, today I’m calling on Utahans to join me in supporting commonsense solutions, working together to protect the mental health of our young people,” Republican Gov. Spencer Cox said in a speech in 2022.

He signed the first restrictions into law in March 2023. They included banning kids under age 18 from using social media between 10:30 p.m. and 6:30 a.m. and requiring age verification for all new accounts. (Tech companies immediately challenged these in court, and they have since been revised.)

What has unfolded throughout North America since then has been a three-pronged strategy: legislation and school policies that attempt to reduce the time children spend on their phones, lawsuits against social media companies, and broader awareness campaigns for parents and kids.

“There are different models of accomplishing change, and I think we’re going to need all of them here, legislative, public, school boards, litigation, everything that can be brought to bear on this to create the change that we need to see,” says Duncan Embury, lawyer for a coalition of school boards in Ontario suing social media companies in a first-of-its-kind case in Canada.

Nancy Crawford is the chair of the Toronto Catholic District School Board, and for the past 14 years she’s watched how students have been changing.

She says their attachment to tech is something that has worried her again and again. From her office in the building of the Cardinal Carter Academy for the Arts, she describes observing high schoolers crouched over their phones outside at the end of a school day. Even in the warmth of late spring, she says, this takes priority over talking to their peers face-to-face.

She worries about the ever-present technology that surrounds her grandchildren as they grow up in this era.

“What happened to books?” she says. “What happened to them running around outside? It’s become increasingly obvious that something’s not good here.”

So Ms. Crawford’s Catholic school district has become one of 12 public school boards and two private schools in Ontario that have joined Canada’s first school-driven lawsuit against social media companies.

The lawsuit, filed this spring, accuses three tech giants of knowingly creating addictive social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok. These 14 Ontario schools and school boards allege these applications have compromised students’ ability to learn and are creating increasing mental health harms.

“Most court cases don’t affect this many people, this deeply,” says Mr. Embury.

So far, Ontario has been the only Canadian province to take such action. But in the U.S., such litigation has exploded over the past year.

At least 44 U.S. states have filed lawsuits against social media companies. Separately, more than 200 American public school districts have also filed similar lawsuits.

The legal arguments are generally similar: They accuse the Big Tech companies of intentionally designing highly addictive products and then marketing them to children and teens, those most vulnerable to emotional manipulation.

Ontario Premier Doug Ford, a successful businessman, thinks the school board lawsuits are unnecessary and that schools should focus on education. “Let’s focus on math, reading and writing,” he said in the spring when the Ontario case was filed.

At almost the same time, however, his administration embraced the legislative approach, passing province-wide rules that limit students’ use of their smartphones.

As of this September, these rules will require that all phones in Ontario schools be kept on silent and hidden from view, except between classes and during lunch. In elementary schools, phones must be silent and out of view the entire day.

A ninth grader places her phone into a holder on the wall as she enters class at Delta High School in Delta, Utah, Feb. 23, 2024.

Paul Davis, a social media expert and activist in Ontario, has made a living talking about the dangers these applications pose to children. But he says lawsuits like those the Ontario school districts have filed are frivolous, and he’s been a critic of a lot of the legal efforts happening.

He worries that the province’s new smartphone ban is less restrictive than the rules some principals have already implemented – thus undermining local efforts already underway.

“We don’t need a lawsuit,” says Mr. Davis, taking a pause at a coffee shop outside Toronto before heading into back-to-back presentations scheduled later in the day. “We need no phones in elementary school, zero tolerance. And we need no kid on social media until 13.”

He’s been sharing this message for the past 13 years, visiting schools and talking to kids and educators about the risks phones pose and what to do about it. And he’s clear on who must take control: parents.

“We are giving our children far too much at a young age,” says Mr. Davis, who’s delivered a TED Talk on the topic. “Parents don’t quite understand how much power is in that device that’s in their child’s hands.”

Matthew Johnson, director of education at MediaSmarts, a digital literacy organization in Ottawa, Ontario, also focuses on parents. He says they are in part to blame. Many don’t regulate their own social media habits, let alone their children’s.

Two-thirds of young people report it was their parents who gave them their first phone, his organization’s latest annual survey found. The reason most give is so parents can contact them at any time.

But the concern for the safety and location of their children clashes with the unintended side effects these powerful communication devices create, he says. This includes the isolation of phone use in lieu of exploring physical spaces.

“At first parents were more often concerned about quite uncommon and extreme experiences like stranger contact and online predators,” he says. “And that changed over time to be focused on the more common but fairly significant things like cyberbullying and online disinformation and hate content.

“And more recently, we’re seeing concerns just generally about simply the amount of time they’re spending on their phones,” Mr. Johnson says.

Two teen sisters keep their smartphones close while having dinner in New York, Jan. 27, 2024.

Some see in the current reactions to social media the same kind of moral panics in both countries at the onset of television or, more recently, video games. And while parents are no longer going it alone to limit their children’s access to social media, some critics argue they should be: This is a matter for the home.

Experts like Mr. Johnson also worry about the focus on addiction, which he believes distracts people from the real issues.

“Unfortunately, there is a tendency to default to the addiction framing,” he says. “And this is a really counterproductive framing, because what it really does is it absolves us of responsibility,” he says. “It says that the device or the app is the problem, not us. It says that we have no control.”

A breaking point

When Liddy Johnson was in seventh grade in South Weber, Utah, right at the top of her Christmas list was, no surprise, a smartphone. She was overjoyed when her parents obliged.

They restricted her from every social media app except Pinterest, however. Her parents felt the popular app had a good enough reputation as an “inspiration board” for cooking and crafts.

These stringent parental restrictions also included a digital curfew. But what began as occasional scrolls through Pinterest soon morphed into hours of surfing each day, says Liddy, now 16 years old. And it wasn’t long before she discovered how to post videos on the site.

“All of a sudden, people were noticing me,” she says. The “likes” were emotionally intoxicating, fueling a need for what she describes as “fake validation.” She began to withdraw from family and friends. She watched her grades suffer. She started fighting more with her parents.

“Everyone was just so angry at me for not wanting to do anything,” she says. “And I was angry at myself.”

Then, in her first few months in high school, she reached a breaking point. After an argument with her mother one morning, she confessed to breaking her parents’ phone rules. She was constantly craving access to social media, she told her, all while feeling depressed to the point of thoughts of suicide.

Her mom took her for a drive. They ended up at a diner, where the high school first-year student sobbed over eggs. She handed her phone to her mother, and agreed to go to therapy.

This moment, after nearly two years of watching her daughter slip into isolation, provided some clarity. She had a serious social media addiction.

“It all clicked,” says Corinne Johnson, Liddy’s mother. “Of course. This makes complete sense,” she remembers thinking after her daughter’s confession at the diner.

Jackie Valley/The Christian Science Monitor

Liddy Johnson (at left) holds up the flip phone that replaced her smartphone after she confessed to her mother, Corinne Johnson (at right), that she felt addicted to social media.

The senior policy adviser for a Salt Lake County Council member, Ms. Johnson is also the president and co-founder of Utah Parents United, a conservative advocacy group for parental rights. She’s been working to support Utah’s legislative efforts to address what she’s experienced firsthand as a serious problem.

Normally, her nonprofit seeks to keep the government out of decisions that it believes should be reserved for parents alone. But now it’s become a mantra for Ms. Johnson, the governor, and other lawmakers: This problem is too big for parents alone.

“We did, as an organization, realize there are times and places where we need the support of our government to hold Big Tech and billion-dollar companies, who view our children as products, accountable,” Ms. Johnson says.

The U.S. surgeon general, Dr. Vivek Murthy, issued an advisory last year that warned of the “growing evidence” that links growing mental health problems to the amount of social media children and teens consume.

Nearly one-third of adolescents report using screens until midnight or later on weekdays, mostly scrolling social media, the advisory noted, citing a number of published studies. One-third of girls reported that they felt “addicted” to their social media apps.

On top of that, nearly half of all children between ages 13 and 17 say social media makes them feel worse about their bodies. Another two-thirds report they’re often exposed to hate-based content on their apps.

Given this growing evidence, Dr. Murthy this summer called for a surgeon general’s warning label to be posted on social media platforms.

The surgeon general’s advisory also coincided with the publication of Jonathan Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness,” a New York Times bestselling book that observers say has put a chill in parental hearts.

Mr. Haidt argued that this generation, smartphone in hand, is at once the most overprotected and the least protected. Overprotected from the “real world” but left alone in a vast, wild, and dangerous world online.

In February this year, Liddy testified about the dangerous spiral she experienced before a Utah House committee, sharing her story in support of legal restrictions on social media use. She’s hoping to spare others from what she experienced.

“It costs government more money when you have kids with major mental health issues,” says Aimee Winder Newton, senior adviser to Governor Cox and director of the Office of Families. “And when you have people who end up in the criminal justice system or end up in poverty and homelessness, those are drains on government.”

Liddy says she feels fortunate to have climbed out of her social media obsession. These days she owns a basic flip phone featuring a flowery case. She rarely texts her friends. But she’s even more old-school than that now:

“Instead, I plan times to hang out with them,” she says.

A new solution: magnetically-locked phone pouches

Granger High School in West Valley City, Utah, has implemented a relatively new approach to restricting the use of smartphones: locking them away in a specially designed pouch that students keep with them.

Jake Crandall/Montgomery Advertiser/USA Today Network/Reuters/File

A pouch made by the California-based company Yondr sits in a student’s backpack at Percy Julian High School in Montgomery, Alabama.

Tyler Howe, principal of the 3,500-student school, does not want this innovative approach to be labeled a “ban,” however. That wording denotes a negative connotation, he says. The reality might be very positive for students, and he hopes the locked pouches will create a “phone-free environment” that spans bell to bell.

Designed by the California-based company Yondr, these soft pouches seal students’ phones inside with a magnetic lock. While Granger requires students to keep their phones locked the entire school day, in other schools, students can disengage these locks at designated “unlocking bases” in unrestricted areas. These pouches have also been used at concerts and comedy clubs.

But Mr. Howe hopes he will see fewer students bowing over their devices in the hallways and at lunch. In other words, it’s not just about reducing distractions in the classroom.

“We want to see healthy, embodied relationships and the communication that happens face-to-face, smile to smiles,” he says.

While school districts have been in many ways leading the litigation against Big Tech companies, they have also been at the forefront on the ground in trying to find the right policies to limit access to social media during school.

States are trying to help, again with legislation. Florida last year passed a law requiring all public school districts to ban cellphone use in the classroom. Louisiana and South Carolina did the same. States such as Indiana, Ohio, and Virginia require districts to have policies limiting student phone use.

Many school districts are acting on their own. Large school districts in Las Vegas and Los Angeles have announced more restrictive cellphone policies. New York City, the nation’s largest school district with 1.1 million students, is planning to ban all cellphone use during the school day, starting next year. State leaders in New York, too, are considering similar statewide measures.

Students at Washington Junior High School use the unlocking mechanism to open their magnetically-sealed phones, in Washington, Pennsylvania.

But the tech companies are fighting back. At the end of last year, under the aegis of the trade group NetChoice, the companies countersued Utah’s pioneering laws, arguing that while well-intentioned, their restrictions were unconstitutional, restricting access to public content, compromising data security, and undermining parental rights.

This forced Utah to scale back some of its efforts to limit kids’ use of social media in the evenings and require age verification measures. “Whether we had the perfect bill or not, we expected legal challenges,” says Senator Cullimore, a floor sponsor for the legislation.

The revised bill requires social media companies to disable addictive scrolling features, boost privacy settings, and arm parents with more tools to monitor and limit their children’s time on the apps.

Opponents haven’t backed down. NetChoice updated its lawsuit after Utah’s revised legislation this year.

“Utahans – not the government – should be able to determine how they and their families use technology,” said Chris Marchese, director of the NetChoice Litigation Center, in a statement announcing its revisions.

At the end of July this year, however, the U.S. federal government joined the massive fray when the Senate overwhelmingly passed 91 to 3 a bill that would force social media companies to take reasonable steps to prevent harm and exercise a “duty of care” to protect children.

Despite this lopsided bipartisan support, the bill faces fierce resistance from tech companies. It also has drawn deep concerns from free speech advocates like those at the American Civil Liberties Union, who argue these measures would chill individual expression and harm marginalized groups.

Earlier this year, Canada, meanwhile, introduced its own nationwide Online Harms Act, which attempts to reduce harmful content on social media sites.

Some younger people, not surprisingly, are also a bit skeptical of the absolutes they are hearing in the debate. Canadian Liv Miller knows how powerful social media is. As a middle schooler, when she got her first digital device, she remembers having to navigate new social norms in friend groups.

Some of the lessons were hard. She was harassed online after she founded a mental health initiative called Bridges of Hope. But today she works for Jack.org, a charity empowering youth to tackle mental health challenges, and she uses social media often to advocate for mental health resources for young people.

It has been a lifeline for LGBTQ+ communities in rural areas, for example. And schools and workplaces increasingly demand a high level of social media savvy.

“I think we should be empowering youth to be part of these conversations, giving them space to say, ‘Well, actually, that is what my boundaries are,’ because they are experts in their own experience,” Ms. Miller says.

American Charlie Bartels, heading to Ohio University this fall, agrees that apps are not the problem. She recalls scrolling on social media for up to six hours a day in middle school, fixating on photos of women who seemed impossibly thin. She wished to be like them. But she says these are conversations for parents, teachers, and kids.

“If your kids are struggling with body issues and your first concern is, ‘What’s wrong with the app?’ and not, ‘Why didn’t they feel like they could talk to me?’ – that’s a problem,” Ms. Bartels says.

“When politicians are like, ‘This app is ruining my kids’ – have you talked to your kids this week? Have you had a meaningful conversation this week?”

At the Cullimore household in Utah, conversations about social media arise more often than the senator’s kids probably want. But they’re still allowed to use their phones.

For the younger children, that generally means surfing YouTube. The older siblings have progressed to mostly using Instagram, TikTok, and Snapchat.

Kynda, now 18 years old and in college, says she supports the Utah legislation her father sponsored. “I feel like that could be really helpful with a lot of things,” she says, mentioning the ability to complete homework without constant distractions.

Utah’s new social media restrictions are set to be in place Oct. 1 this year. Kapri’s not so sure schools need to entirely banish phones, though.

“In class, I get it because it’s kind of disrespectful,” the 16-year-old says. “But I feel like if we’re just having our free time, we should be able to have our phone.” Still, she adds, “When we’re with our friends, we try and not be on our phones.”

Unless they’re filming a TikTok dance.

Staff writer Danish Bajwa contributed reporting from Boston.